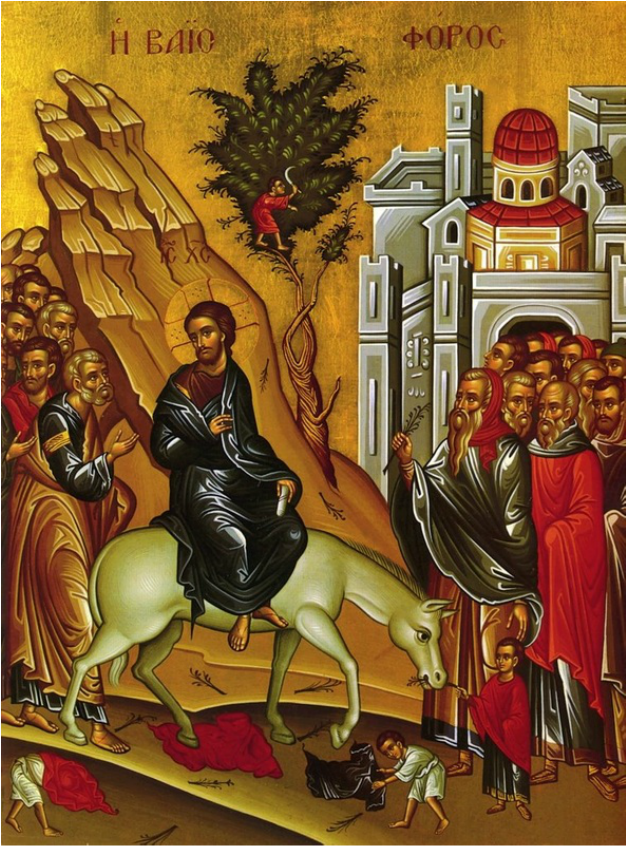

I am innocent of the blood of this just person: see you to it. (St. Matthew 27. 24) We in the Christian church are called to silence and contemplation during Holy Week. The silence is our response to the Passion and Crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth, the Son of God. Holy Week has been set aside from the time of early Church ponder our Lord’s suffering in silence. If we approach this time with a diligent and determined concentration, we will, no doubt, find that it will simultaneously assault and confound our human reason, and tear and wrench the human heart from the objects of persistent and protracted lesser loves. Should we persevere in faith with our eyes on Jesus Christ, God’s great unseen eternal design will begin to unfold before our eyes through the suffering and Passion of the Word made flesh. And yet the task that we set before ourselves today seems so daunting. No sooner have I said that we must be still and silent, than we are overwhelmed and swept up in the tumultuous commotion and confusion that surrounds the trial of Jesus Christ. Pontius Pilate, the Prefect or Roman Governor of Judaea, is trying to superimpose order and discipline on chaos and confusion, on what he thinks is merely a small-town problem whose incommodious clutter must be calmed and contained. He seems a reasonable and just enough man, who is neither intrigued nor impressed by the religion of the Jews. If anything, he is perturbed that a matter of such provincial color should dare to disturb the Pax Romana –the Roman Peace, which he is paid handsomely to maintain as Caesar’s Viceroy. His sense of Roman honor and decency is offended when he learns that the rag-tag rabble of Jewish Temple guards has harassed, rustled, and bound this Jesus of Nazareth with blatant disregard for Roman Law. So he cannot ignore this threat to the Roman Peace. The Jewish temple priests and chief elders have roused and excited the plebs, or the mob of unemployed and disgruntled men who had hailed Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem –Hosanna to the Son of David, Blessed is He that cometh in the name of the Lord…., pinning their hopes on Him as the great freedom fighter who would break the yoke of Roman oppression. Finding that He was not prepared to use any of those miraculous powers they had seen in His healing of the diseased to call down God’s wrath on the Romans, they had turned on Him. Pilate is thus justifiably nervous. So, in the interest of Roman Law, Pilate questions this Jesus who now stands before him. Art thou the king of the Jews? (St. Matthew xxvii. 11) Jesus answers, Thou sayest, or So you say. (Idem) The Jews accuse him of many things, and Jesus remains silent. Pilate asks again, Hearest not how many things they witness against thee? (Ibid, 13) Jesus’ silence confounds and unsettles Pilate, so that the governor marveled greatly. (Ibid, 13, 14) But Pilate is pressured on another front to maintain the Pax Romana. To placate the plebs, it was his custom, yearly on the Feast of the Passover, to pardon and liberate one of their own. There was a notorious criminal in custody that year, one Barabbas, whose name means, ironically enough, son of the Father. Pilate knew that out of envy and malice the mob had delivered Jesus to him, and also guesses that they have no interest in the release of Barabbas, since radical insurrectionists threatened the protection of the Jewish establishment as much as the peace of Caesar’s Empire. Perhaps he could pit the chief priests and scribes against the mob, and thus sow discord amongst the Jews. So he asks the Jews, Whom will ye that I release unto you? Barabbas, or Jesus which is called Christ? (Ibid, 17) Having asked the question, he sits down on the judgment seat. No sooner has he done this than matters become more complicated by a message that he receives from his wife, Claudia Procula. Do not meddle with this innocent man; I dreamed today that I suffered much on his account. (R. Knox, Ibid, 19) Romano Guardini tells us that, Pilate is skeptical but sensitive –possibly also superstitious. He feels the mystery, fears supernatural power, and would like to free [Jesus]. (The Lord, p. 392) But the chief priests and elders have joined with the mob to demand Barabas’ release and Jesus’ death. Pilate’s conscience is nevertheless disturbed, and so asks, Why, what evil hath [this Jesus] done? (St. Matthew 27. Crucify him, they cry with vehemence. Pilate surrenders to their wish our of fear. Then he took water and washed his hands before the multitude, saying, I am innocent of the blood of this just person: see you to it. (St. Matthew 27. 24) The Roman Peace is maintained for a season. The Jews take responsibility: His blood be on us, an on our children. (St. Matthew 27. 25) Now I have said that we must be still and silent this coming week in order to be touched and moved by the Word of God in heart of Jesus. But what should touch and move us most is Jesus’ relative silence through His suffering and death. Now, you say, but of course He was relatively silent; He was having the life beaten out of Him. This is true enough. Pilate’s violent soldiers and the vengeful Jews were determined to silence this Jesus of Nazareth forever. Extreme torture has a way of beating the life out of even the bravest of heroes. But Jesus will not die the tragic hero of an ancient epic. His silence invites us into the articulated truth of His innermost being. Again, as Romano Guardini says, It is frightening to witness this hate-torn world suddenly united for one brief hour, against Jesus. And what does He do? Every trial is in reality a struggle –but not this one. Jesus refuses to fight. He proves nothing. He denies nothing. He attacks nothing. Instead, He stands by and lets events run their course –more, at the proper moment He says precisely what is necessary for his conviction. His words and attitude have nothing to do with the logic or demands of a defense. The source lies elsewhere. The accused makes no attempt to hinder what is to come; but His silence is neither that of weakness nor of desperation. It is divine reality; full, holy consciousness of the approaching hour; perfect readiness. His silence brings into being what is to be. (Ibid, 395) God’s Word does not respond with evil for evil. God’s Word will overcome evil with His own natural goodness. But first, He must allow sin to do its worst against God. It is only when God in the flesh allows and suffers this that man can come to understand the power and capability and then the impotence and limitation of evil. God’s Wisdom will reveal that evil cannot stop Love’s remaking of human nature with either sin or death. Christ will call man into His suffering and death and consecrate them as the first steps of a journey back into new life. In the midst of His agony, He calls us forth into ecstasy: I love you. I want you. I desire for you to be healed in soul that you might go and sin no more. And this He says in response to those who are determined only to spread the contagion of their darkness. Only His eyes are all seeing and they see through the ground of all depravity. Jesus…knows about sins as God knows –hence the awful transparency of His knowledge. Hence His immeasurable loneliness. He is really the Seer among the blind, sole sensitive one among beings who have lost touch, the only free [man]…in the midst of confusion. So what I hope we shall hear in the still and silent Jesus Christ this week is the Word of God’s Love still hard at work His suffering and dying to sin. Jesus suffers mostly for those who will never see that their sin can separate them forever from God’s desire. In loving them He mourns and suffers for their practical atheism. The work of salvation must proceed with or without them. This breaks the human heart of Christ. Yet the human heart must be broken of any expectations from sinners and their sin. The human heart must be broken open in utter abandonment to God’s wisdom, love, and power alone. Thus out of silence Jesus speaks: You have stripped, bound, whipped, and tortured me. You have nailed my hands and feet to the tree. You continue to tempt, taunt, and provoke me. And do you think that I am any less free to do the will of my Father who sent me? I made this body that I inhabit, and I made yours too. Do you think that my suffering and your rejection of God will stop the progress of God’s Word of Love in me? I tell you, that because I am still loving and forgiving the progress of salvation proceeds apace. Through all of this suffering and death that you have demanded of me, still I desire you. In the midst of this suffering and death, caused by your sin, I am making all things new. In fact this suffering and death make my love more intensively loving. On this day I have accepted your judgment of God’s Word in the flesh that I AM. You can kill my humanity. It is yours also. But my love is already set on taking this death and molding it into an occasion for new and joyous life in me for you. ‘Behold I make all things new.’ Dear friends, this day, in stillness and silence, let us see how this Word of God can still be heard as the one who hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows…[who] was wounded for our transgressions…[and]bruised for our iniquities: [through whose] stripes we are healed. (Is. liii. 4,5) Let us hear that from His heart to ours God’s Word always communicates His living love to us. He expresses it to us as He dies for us on His Cross, and He longs to make His death our own. So let us pray that we might embrace that love that went to the precipice of the abyss for us, to the border of nothingness, in a suffering that endures the cumulative effect of our collective sin. And in His suffering the effects of this sin on the Cross, let us begin to sense how His love is already inviting us out of it and into the new and marvelous life of virtue that will carry us to His kingdom. So let us begin to learn this truth about Christ’s death: It wins a trumph over earth’s despair It turns to truth life’s failing prophesy, It tells us that the Lord of Heaven was brave, And strong and resolute in love to save The world that He had made. Amen. ©wjsmartin  Summa: II, ii, 148, 1. Article 1. Whether gluttony is a sin? Objection 1. It would seem that gluttony is not a sin. For our Lord said: Not that which goeth into the mouth defileth a man. (St. Matt. xv. 11) Now gluttony regards food which goes into a man. Therefore, since every sin defiles a man, it seems that gluttony is not a sin. Gluttony should not be considered as a sin since it relates to what goes into and does not come out of a man. Since no external and visible created thing is evil but good by nature because created by God, gluttony should not be considered a sin by reason of its object. Objection 2. Further, No man sins in what he cannot avoid (Ep. lxxi, ad Lucin). Now gluttony is immoderation in food; and man cannot avoid this, for Gregory says: Since in eating pleasure and necessity go together, we fail to discern between the call of necessity and the seduction of pleasure (Moralia, xxx. 18), and Augustine say, Who is it, Lord, that does not eat a little more than necessary? (Confessions x, 31) Therefore gluttony is not a sin. Because gluttony relates to a natural and necessary appetite, it should not be counted as a sin. Every man falls and stumbles in the presence of good food or fine wine. Man needs to eat to survive and so can rarely differentiate between what is needed and what is desired. Because this particular good is so necessary a man for whom it easily becomes his delight cannot be accounted sinful. Objection 3. Further, in every kind of sin the first movement is a sin. But the first movement in taking food is not a sin, else hunger and thirst would be sinful. Therefore gluttony is not a sin. The first movement in any sin is the cause of the sin. It would appear that the first cause in eating is hunger and thirst. Hunger and thirst are necessary causes of a man’s perfection of his whole nature. Therefore gluttony is not a sin. On the contrary, Gregory says that unless we first tame the enemy dwelling within us, namely our gluttonous appetite, we have not even stood up to engage in the spiritual combat. (Moralia. xxx. 18) But man's inward enemy is sin. Therefore gluttony is a sin. Appetite is not a sin. Exaggerated appetite is a sin. Unless we begin to find the mean between the extremes of gorging and fasting, our bodies shall not be conditioned properly to house the soul that is made to seek after God. The problem is not with appetite per se but with the internal enemy that would drive appetite to an extreme expression. The inward enemy is the spirit that perverts and corrupts the appetite. I answer that, Gluttony denotes, not any desire of eating and drinking, but an inordinate desire. Now desire is said to be inordinate through leaving the order of reason, wherein the good of moral virtue consists: and a thing is said to be a sin through being contrary to virtue. Wherefore it is evident that gluttony is a sin. So Gluttony is an expression of an intemperate or overindulgent will. When the will and its desire are ‘inordinate’, a man ignores the rational end for which the natural good of the body is pursued and so exaggerates its need. So rather than ordering his relation to food and drink, he rashly and impetuously overindulges them. The cause is normally a kind of irrational intention to procure from them what they have forfeited in the loss of reason, i.e. some kind of imitation of divine satisfaction. Such is, of course, not only irrational but insane. Thus, gluttony (and drunkenness) is a sin. Reply to Objection 1. That which goes into man by way of food, by reason of its substance and nature, does not defile a man spiritually. But the Jews, against whom our Lord is speaking, and the Manichees deemed certain foods to make a man unclean, not on account of their signification, but by reason of their nature. It is the inordinate desire of food that defiles a man spiritually. The Jews and Manichees deem certain foods to be evil in nature. No food is evil in nature since all food comes from God’s good creation of it. But to make food or drink into evil natures is just as sinful as making an idol out of them. Food and drink are necessary to the redemption of the whole person in so far as they enable a man to survive for long enough to seek God, find Him, and become right with Him. So both those who abstain from food and drink because they are deemed evil and also those who overindulge them because they are ‘too good’ are to be counted guilty of gluttony. Reply to Objection 2. As stated above, the vice of gluttony does not regard the substance of food, but in the desire thereof not being regulated by reason. Wherefore if a man exceed in quantity of food, not from desire of food, but through deeming it necessary to him, this pertains, not to gluttony, but to some kind of inexperience. It is a case of gluttony only when a man knowingly exceeds the measure in eating, from a desire for the pleasures of the palate. Those who overeat and overdrink are often transparently aware of their sin. So they knowingly overeat and overdrink. Otherwise they wouldn’t be closeted over-eaters and over-drinkers. In public such people often eat or drink less. Such is an outward and visible sign that the sins of gluttony loom large within their souls. But ‘what they do in secret is known openly.’ So they habituate their palates to an overdependence upon food or drink. Thus a basic need become a desire and the body becomes dependent upon a false god. Reply to Objection 3. The appetite is twofold. There is the natural appetite, which belongs to the powers of the vegetative soul. On these powers virtue and vice are impossible, since they cannot be subject to reason; wherefore the appetitive power is differentiated from the powers of secretion, digestion, and excretion, and to it hunger and thirst are to be referred. Besides this there is another, the sensitive appetite, and it is in the concupiscence of this appetite that the vice of gluttony consists. Hence the first movement of gluttony denotes inordinateness in the sensitive appetite, and this is not without sin. The first movement of gluttony is not found in the vegetative soul but in the sensitive soul. The vegetative soul is the seat of instinctually present needs or bodily appetites. The sensitive soul is the seat of the powers of perception and willful movement. Here a man has the power of imagination, common sense, evaluation and estimation, and memory. So through the sensitive soul a man can, to a degree, order his relation to the external world. Were he to trust his senses wholly he would neither over-eat nor over-drink since he would remember that they make him sick. But the habituation to intemperance has a strange effect upon the mind which jumps to delight against pain and pleasure. Thus a man perverts his sensitive appetite through a contortion of reason. The corporeal world has been exaggerated by reason that dissociates delight from necessity. So the sensitive soul as mediator between the rational and vegetative souls is corrupted. Thus gluttony is a sin. ©wjsmartin  Summa: II, ii, 118, iv. Article 1. Whether covetousness is a sin? Objection 1. It seems that covetousness is not a sin. For covetousness [avaritia] denotes a certain greed for gold [aeris aviditas*], because, to wit, it consists in a desire for money, under which all external goods may be comprised. [The Latin for covetousness "avaritia" is derived from "aveo" to desire; but the Greek philargyria signifies literally “love of money": and it is to this that St. Thomas is alluding here]. Now it is not a sin to desire external goods: since man desires them naturally, both because they are naturally subject to man, and because by their means man’s life is sustained (for which reason they are spoken of as his substance). Therefore covetousness is not a sin. It would appear that covetousness is mere desire for the gold that buys the goods that a man needs in order to sustain his earthly existence. Since money is necessary for procuring the natural goods needed for survival, the love of money is love of a means, and thus avarice or covetousness is not a sin. Objection 2. Further, every sin is against either God, or one's neighbor, or oneself. But covetousness is not, properly speaking, a sin against God: since it is opposed neither to religion nor to the theological virtues, by which man is directed to God. Nor again is it a sin against oneself, for this pertains properly to gluttony or lust, of which the Apostle says He that committeth fornication sinneth against his own body. (1 Cor. vi. 18) On like manner neither is it apparently a sin against one's neighbor, since a man harms no one by keeping what is his own. Therefore covetousness is not a sin. The desire or love for money is not harmful in any religious or theological sense. It stands against neither religion nor the theological virtues. It does not engender sin against God since it is unrelated to theological virtue. Nor is it a sin against oneself, for to sin against oneself involves the sins of gluttony and lust, whereby a man dishonors and disrespects his body. Nor does it appear to be a sin against one’s neighbor, since what is one’s own cannot harm others. Objection 3. Further, things that occur naturally are not sins. Now covetousness comes naturally to old age and every kind of defect, according to the Philosopher (Nic. Ethics, iv. 1) . Therefore covetousness is not a sin. Avarice or greed is merely a natural kind of habit that develops over time as men grow in age. Thus a man seems to become overly concerned with his money and his earthly fortune as he approaches the twilight of human life. Naturally he is worried that he might not have enough. So avarice or love of money is merely a natural habit or custom in life that accompanies the weakness and uncertainty of advanced maturity. On the contrary, It is written: Let your manners be without covetousness, contented with such things as you have. (Hebr. xiii. 5) I answer that, In whatever things good consists in a due measure, evil must of necessity ensue through excess or deficiency of that measure. Now in all things that are for an end, the good consists in a certain measure: since whatever is directed to an end must needs be commensurate with the end, as, for instance, medicine is commensurate with health, as the Philosopher observes (Politics, i. 6). External goods come under the head of things useful for an end. Hence it must needs be that man’s good in their respect consists in a certain measure, in other words, that man seeks, according to a certain measure, to have external riches, in so far as they are necessary for him to live in keeping with his condition of life. Wherefore it will be a sin for him to exceed this measure, by wishing to acquire or keep them immoderately. This is what is meant by covetousness, which is defined as immoderate love of possessions. It is therefore evident that covetousness is a sin. Evil is an excess or deficiency in some expressed desire or voluntary habit. And so the good consists in a proper relation to sought after ends. The good is found in a man’s measured relation to the ends which he needs for his well being. External things are useful for an end, that is, they serve and fulfill necessary needs in man’s life. Therefore, in this case, man needs the external good of riches in order to sustain his existence. External riches enable him to procure food, drink, lodging, clothing, and so forth. Nevertheless, to desire more than one needs in an immoderate and excessive way, is sinful. Thus a man ought not to possess more than he needs for his bodily health and well being. If he desires to obtain, possess, hoard, or spend more than he needs, he is covetous, greedy, or avaricious. Such a desire is immoderate and excessive. Money, mammon, or earthly treasure has then taken on the nature of a false god. Again, a man commits the mortal sin of covetousness if he desires too much for himself. Clearly he is then standing against the intrusion of true charity in his life, and thus will be in danger of hell fire and damnation. Reply to Objection 1. It is natural for man to desire external things as means to an end: wherefore this desire is devoid of sin, in so far as it is held in check by the rule taken from the nature of the end. But covetousness exceeds this rule, and therefore is a sin. The desire for external things is necessary. But should a man seek to have or hold what is excessive or beyond what he needs, he sins. Here he sins against his knowledge of God’s munificence and charity and thus threatens God’s perfection of his own life. He sins too against others since what he does not need might be given to those who do, thus contributing to a much more equitable dispersal of the riches of this world. Reply to Objection 2. Covetousness may signify immoderation about external things in two ways. First, so as to regard immediately the acquisition and keeping of such things, when, to wit, a man acquires or keeps them more than is due. On this way it is a sin directly against one's neighbor, since one man cannot over-abound in external riches, without another man lacking them, for temporal goods cannot be possessed by many at the same time. Secondly, it may signify immoderation in the internal affection which a man has for riches when, for instance, a man loves them, desires them, or delights in them, immoderately. On this way by covetousness a man sins against himself, because it causes disorder in his affections, though not in his body as do the sins of the flesh. As a consequence, however, it is a sin against God, just as all mortal sins, inasmuch as man contemns things eternal for the sake of temporal things. When one man superabounds in external riches, it is always the case that another has much less. The plenty of one means the privation of others. Temporal goods are limited in quantity. A limitation of quantity means that more for one is less for others. Avarice, Greed, and covetousness inevitably mean that others are deprived. The avaricious, greedy, or covetous man is often oblivious to the fact that he is a hoarder or spendthrift. He concludes that he is hurting no one. But from the standpoint of Christ if a man fails to help another, he is withholding himself from virtue and thus perfecting real vice. So the man who is not sharing his wealth with others liberally is corrupting himself and hurting his neighbor. In addition, a man hurts himself when he indulges his own riches and loves them more than he should. The question that the greedy, avaricious, or covetous man must ask is this: Do I need all that I have? Am I enjoying mammon when it ought to be taken off my hands and spread around so that it ceases to be the false god than it has become for me? Love of one’s own riches corrupts the possessor’s heart and affection. Love of one’s own treasure inevitably threatens the health of the soul, since the soul is clearly moved and defined more by filthy lucre than by Divine riches and eternal virtues. This sin is one against God since it foolishly reveals the neglect of duty to God in the failure to love Him above all things and through the same love to have all things in common, as much as possible, with other men. Reply to Objection 3. Natural inclinations should be regulated according to reason, which is the governing power in human nature. Hence though old people seek more greedily the aid of external things, just as everyone that is in need seeks to have his need supplied, they are not excused from sin if they exceed this due measure of reason with regard to riches. Age is no excuse for indulging inordinate love of riches. Age is no excuse for becoming a mean spirted hoarder of what ought to be given freely to others. When a man reaches his old age, he ought to be giving what he has to those in need. When a man reaches old age, he should be so moved by the love of God that any calculated stinginess or accumulation of wealth ought to be seen as the greatest threat to a soul that needs the love from God more than all else. To secure the love of God for eternity, a man must have given liberally to all others as God has given to him. ©wjsmartin  But Jerusalem which is above is free, which is the mother of us all. (Gal. iv. 26) At the very beginning of Lent Jesus said to his disciples, Behold we go up to Jerusalem. (St. Luke xviii. 31) We began our journey at Christ's command. Long journeys are hard work, and this Lenten journey is no short trip. For nearly some seven weeks Christians are invited to walk with Jesus towards Jerusalem. Walking to Jerusalem is what our lives are all about. We walk with Jesus in order to see how he conquers the temptations of Satan and triumphs over sin for us. We walk with Jesus to discover that, like the woman of Canaan, we are more like dogs than men, aliens and exiles to God’s promises, and yet wholly hanging upon crumbs that fall from His table. So we learn to become humble and obedient and to persist in the reception of Jesus' mercy and healing. As dogs, we learn also that we are, more often than not, dumb and mute, incapable of comprehending and articulating God’s Word and will in our lives until His inward Grace liberates our spiritual senses. Our Lenten pilgrimage with Jesus up to Jerusalem, (St. Matthew xx. 18) will not be easy. We learn much about ourselves on this journey, and so we become spiritually exhausted. We grow weary, peckish, and perhaps even a bit chapfallen. Lenten fasting and abstinence do that to a person. At times we become distracted and even lose our way. The pull and tug of certain temptations may well have been overcome, but seven other demons worse than ourselves threaten to consume us. (St. Matthew xii. 45) Satan realizes that he is losing our spirits, and so he attacks our bodies with renewed vigor through the elements of this world. (Galatians iv. 3) We have the best of intentions and yet feel ourselves the children of the proverbial Hagar, the bond woman –mother of an earthly bastard child. We do want to become free men, children of promise, and followers of Jesus, who go up to Jerusalem which is above… and is free. (Galatians iv. 26) And yet it seems the more we try that further back we fall. So today Jesus Christ and His Bride, the Church, provide us with what we need. Today is Dominica Refectionis –Refreshment Sunday. It is also called Mothering Sunday: the day on which Mother Church asks us to sit down and rest awhile, to receive faithfully the spiritual food which will enable us to soldier on so that our fasting and praying, reading Scripture, and following Jesus Christ will not be in vain. Today we are asked to stop and rest awhile and to contemplate Jerusalem which is above… and is free. (Ibid) So we read that Jesus went up into a mountain, and there He sat with His disciples. (St. John vi. 3) Jesus bids us come with Him to the mountain of His holiness so that He might strengthen us for our continuing Lenten journey. He knows that we are in danger of spiritual languor and listlessness. So He intends to provide us with that spiritual food which will give us dogged and dauntless determination to press on.…Jesus said, Make the men sit down. Now there was much grass in the place. So the men sat down, in number about five thousand. (St. John vi. 10) St. John Chrysostom tells us that Jesus calls us up to rest at intervals from the tumults and confusion of common life. For solitude is a thing meet for the study of wisdom. And often doth He go up alone into a mountain, and spend the night there, and pray, to teach us that the man who will come most near to God must be free from all disturbance, and must seek times and places clear of confusion. (St.J.C.: Sermon…) And so we must sit down, listen, and trust. And yet in Lent, worn out as we are, when asked by Jesus, Whence shall we buy bread that [all] these may eat? (St. John vi. 5), our minds jump back to earthly solutions to earthly problems. Jesus asks this question this morning to prove Philip, for he himself knew what he would do. (St. John vi. 6) Jesus intends to enlarge and deepen Philip's faith. Philip has seen the finger of God at work in the miracles that Jesus has performed. Will he believe that Jesus can provide food that no man can find or afford and that can satisfy far more than the physical hunger of a paltry five thousand? What measure of faith does Philip have? Philip answers, as most of us would, as one in bondage to the elements of this world and their measuring rod. He responds that even two-hundred penny worth is not enough for this crowd. (St. John vi. 7) Philip is thinking in earthly terms and thus calculates the monetary cost of feeding the hungry thousands. Too many people, too little money, he conjectures. So Jesus intends to make outward and visible the smallness or poverty of Philip’s faith. His faith should have been in process of enlarging and expanding because the same Jesus who made water into wine at the Wedding in Cana of Galilee would surely be able to feed the hungry multitude. His faith should have seen too that if Christ has asked whence shall we buy bread, that Christ intended to include Himself in procuring the solution. His faith should have trusted finally that Christ alone, whom Philip has already acknowledged as Messiah –Him of whom Moses in the law and the prophets did write (St. John i. 45), is always prepared and able to feed His people with what earthly mammon can never purchase. Philip’s faith is small and weak because of what they do not have. Andrew’s faith is small and weak because of what they do have. There is a young lad who hath five barley loaves and two fishes, but what are they among so many? (St. John vi. 9) As Philip’s faith was overcome by too much, Andrew’s was constrained by too little. To offer so little to so many could only stand to mock them, Andrew thought. True faith can often be destroyed because we conclude that we never have enough or we complain about having too little. Jesus tells us to sit down, listen, and trust. He asks us to remember that we are going up to Jerusalem, that we are dogs eating from the crumbs that fall from His table, and that we must not only hear the Word of God but keep it. Jesus said, Make the men sit down. Now there was much grass in the place. So the men sat down, in number about five thousand. The disciples obey the Master, though as yet they have nothing to set before the guests. Nature serves her Master and so affords Him and his guests a plush, green carpet of cushioned grass. And Jesus took the loaves; and when he had given thanks, he distributed to the disciples, and the disciples to them that were set down; and likewise of the fishes as much as they would. Before we make us of God’s gifts to us, we must give thanks. What He gives to us is more than sufficient to satisfy our hunger. Jesus asks us to entrust our wellbeing to Him as we travel up to the Jerusalem of our salvation. Five loaves and two fishes will feed five thousand. Tiny morsels, fragments, or crumbs that combine with God’s Word will always be sufficient to fill hungry souls. Andrew’s poverty becomes Philip’s plenty. Something small becomes something great. The kingdom of heaven is like to a grain of mustard seed, which a man took, and sowed in his field. (St. Matthew xiii. 31) Which indeed is the least of all seeds: but when it is grown, it is the greatest among herbs, and becometh a tree, so that the birds of the air come and lodge in the branches thereof. (Ibid, 32) Jesus says, gather up the fragments that remain that nothing be lost. (St. John vi. 12) Faith is fed with such spiritual plenty that fragments remain from Christ’s feast –twelve baskets full to feed twelve Apostles and the multitudes in the world that they will convert. Those who think that Jesus Christ comes to satisfy only earthly hunger are in bondage to the elements of this world. (Gal. iv. 3) They are the children of Hagar. They are like Christians who pursue earthly needs and wants to the detriment of their souls. Their faith rests in earthly things and does not enlarge to embrace Christ’s true desire for man. To them nothing remains of Christ’s desire to feed the faith of their souls. But faith’s sustenance is food for men wayfaring. As St. Hilary suggests, The substance [of the five barley loaves and two fishes] progressively increases. (The Passing of the Law: St. Hilary of Poitiers) And as Archbishop Trench says, So we have here a visible symbol of that love which exhausts not itself by loving, but after all its outgoings upon others, multiplies in an ongoing multiplying which is always found in true giving.... (Par’s. p. 213) Christ does not exhaust His loving power merely in provisions for the needs of the flesh. His love intends always to expand and enlarge that faith that will follow Him up to Jerusalem which is above, and is free. (Gal. iv. 26) Therefore the Apostles gathered the fragments together, and filled twelve baskets with the fragments of the five barley loaves, which remained over and above unto them that had eaten. (St. John vi. 13) St. Augustine tells us that the fragments that remained were the parts that the people could not yet eat. (Tr. xxiv. 6) They were not yet strong enough to eat this spiritual food. However, Jesus says, if you follow me, you will desire to eat of these fragments that remain. In the fragments that remain are hidden gifts of mystic meaning. In the fragments are contained the more of God’s food, which Jesus will give to them that hunger and thirst after righteousness. (St. Matthew v. 6) Jesus always provides more and better food to those who follow Him in faith. Faith sees that the more than the multitude can eat is Spirit and is Truth. Within fragments and crumbs of earthly food is the spiritual power of the loving Lord who alone can deliver man to salvation. There is more to be seen, grasped, and ingested of this Giver and His gifts, but not until the eyes of faith are opened and the believer’s heart is softened. Let us then gather up the fragments that nothing be lost. (St. John vi. 12) We will need them, for remember, behold we go up to Jerusalem, and mere earthly fare will never feed and sustain a faith that seeks to behold and plumb the depths of that love that never stops giving. Amen. ©wjsmartin |

St. Michael and All Angels Sermons:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed